This World: Hunter Bear / Dr. John Salter Jr.

One of my American Heroes is Hunter

Gray, also known as Hunter Bear, whose name was Dr. John Salter, Jr., when he taught a class in social justice that

I took at the University of North Dakota. At the time, I was 19, coming out of a small, Minnesota town, and had never met someone

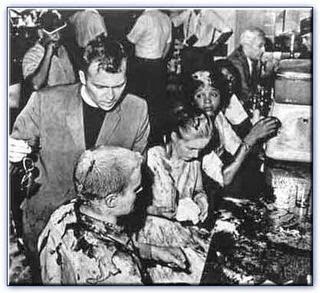

who’d both 1) been a key figure in the national struggle for civil rights, playing a key part in the 1963 Woolrich lunch

counter protests in Jackson, Mississippi (that's him being assaulted in the foreground of the photo at left), and also 2) been “abducted” and studied by friendly beings from another planet. Most

students found him really captivating, or at least quirky and interesting, and

for me, meeting him was challenging—his

life was hard to assimilate. On the one hand, you had to put your body on

the line for causes you believed in; I still have a hard time imagining myself

exhibiting the courage that Salter and his companions Anne Moody and Joan

Trumpauer displayed in Jackson. Then, on the other hand, you could be driving along the highway one

night with your son, and you could experience an episode of mind control that

caused you to travel far off of your planned route into the wooded hills of Wisconsin’s

“Driftless Region” where you’d be pulled over by friendly aliens who would not

only study your body but actually improve it.

One of my American Heroes is Hunter

Gray, also known as Hunter Bear, whose name was Dr. John Salter, Jr., when he taught a class in social justice that

I took at the University of North Dakota. At the time, I was 19, coming out of a small, Minnesota town, and had never met someone

who’d both 1) been a key figure in the national struggle for civil rights, playing a key part in the 1963 Woolrich lunch

counter protests in Jackson, Mississippi (that's him being assaulted in the foreground of the photo at left), and also 2) been “abducted” and studied by friendly beings from another planet. Most

students found him really captivating, or at least quirky and interesting, and

for me, meeting him was challenging—his

life was hard to assimilate. On the one hand, you had to put your body on

the line for causes you believed in; I still have a hard time imagining myself

exhibiting the courage that Salter and his companions Anne Moody and Joan

Trumpauer displayed in Jackson. Then, on the other hand, you could be driving along the highway one

night with your son, and you could experience an episode of mind control that

caused you to travel far off of your planned route into the wooded hills of Wisconsin’s

“Driftless Region” where you’d be pulled over by friendly aliens who would not

only study your body but actually improve it.

Over the years, I think John’s

stories have stayed with me partly as cautions: at no point should I believe

that I’ve got it all figured out. Life’s possibilities are incredibly diverse,

and people like myself, who are fortunate, and whose lives are somewhat

contained and sheltered, shouldn’t be out there trying to tell anyone how it

is.

Also, I think that John’s abduction

story helped me to be open to an experience of contact that I had a few years ago—not with extraterrestrials, but

with the spirit of someone who’d died and who, I believe, made contact with me

for a brief moment (It’s a story I tell in the poem “Memorial,” part of my 2011

collection Absentia). My availability to that experience is

something that connects, when I think about it, to what I valued most about

studying with Dr. Salter: his very simple, but profoundly noticeable, attitude of overt kindness and acceptance. He brought

it to his lectures and to his individual conversations, and it helped make me more open, less prone to pre-judge an experience.

Dr. Salter spoke quietly, although he was a large

man—maybe 6’2 or 6’3—and with commitment, and he smiled in a distinctly curious, generous

way that carried over into his actions. I remember one day a student fell

asleep in his class—Dr. Salter’s speaking style was really very relaxing—and when a couple of other students laughed about it

(I think the guy might’ve actually snored

a little), Dr. Salter noticed. I

remember that he stopped whatever he was saying and spoke even more quietly than usual. “Oh, we

shouldn’t wake him,” he said. “Sleep is very

important. If any of you feel like you need to sleep during this class, you

should absolutely feel welcome to do so. You have to get your sleep.” This was so incredibly kind I thought—almost to a fault, really, right? I mean… students

shouldn’t be sleeping in class,

should they? But that factor of disrespect or

appropriateness slid completely away from Dr.

Salter—no power-based consideration entered his thinking even for a second, it

seemed. And it was doubly ironic because one of the ways that the friendly

extra-terrestrials had improved Dr.

Salter (I think I remember this

correctly) manifested itself as an ability to go without sleeping for long

periods of time. He could sleep if he wanted to, but he didn’t need to sleep more than an hour or so

per day. Still, he realized that the number one thing that particular hung-over late

adolescent slacker needed at that moment was to sleep.

Everything else could wait.

No surprise—he has

continued his activism and social justice work. His

book on the civil rights struggle, Jackson

Mississippi: An American Chronicle of Struggle and Schism, was re-released

by the University of Nebraska Press, he’s been honored by national Native American

organizations for his commitment, and he continues to write and speak about organization and

activism. This, I know, is his real legacy: his unflagging commitment to this world is the most important thing that he has to teach.

But of course I read the account of

his 1988 close encounter with another world, entitled “Friends of the Vast Creation: An Account of the Salter UFO Encounters of March, 1988.” It was a text version of the story he'd told our class that year, inspiring us all to laugh and shake our heads and debate and imagine. Only on this occasion did I realize that I now live just a

few miles from where the encounter occurred. Dear friends of mine have a little

off-the-grid forest and farm property, nestled in a valley just off the highway

where the aliens pulled him over (I wonder if they turned on their sirens…). When I drive out that way, I think of how a good-sized

flying saucer could practically disappear in one of those old coulee crevices

remaining from before the last ice age.

Comments

Post a Comment